Package Filtering

The Problem

Supply chain security is a huge problem in OSS. The great things about OSS, code reuse and modularity, can be taken advantage of to infect large numbers of applications with a single well-placed supply chain attack.

For example, in npm, it's not uncommon for an application with a couple dozen top level dependencies to pull in hundreds or thousands of transitive dependencies via the install process. For web apps, about 97% of the code is pulled in this way, so it’s almost impossible for developers to know the true surface area of the code in their applications.

The security team at npm does the hard work of implicating bad packages, so we know which packages are bad and why. However, we didn't have a way to keep these bad packages from being installed by an unsuspecting developer.

The Solution

The typical developer workflow is to create a package.json file where they

define their top level dependencies. When npm install is run, npm

constructs the dependency tree and fetches all packages (as tarballs) from the

configured upstream registry.

One of these upstream registries is npm Enterprise, our private package hosting solution. Because this product is typically purchased by large companies, there are three personas to consider:

- The npm developer who runs

npm installand searches for packages, but doesn't think about security or administer the services their tools are pointed at. - The npm Enterprise admin who is responsible for making sure developers are productive and configuring the tools those developers depend upon.

- The security team who is responsible for keeping the company and its assets safe from external attacks, which includes setting security policy that developers are expected to comply with.

- The CTO or engineering manager who purchases npm Enterprise based on cost, what it claims to do, and on the recommendation of team members.

We discovered that developers don't want to be blocked, so any solution needs to make it obvious why a package was blocked, and easy to find appropriate replacement packages. The npm Enterprise admins need an easy way to set security policy dictated to them by the security team. The security team needs a way to enforce policy so they don't have to spend time verifying manual compliance, which is very time consuming. Finally, the CTO or engineering manager wants a tool that makes their developers happy and is from a company they trust.

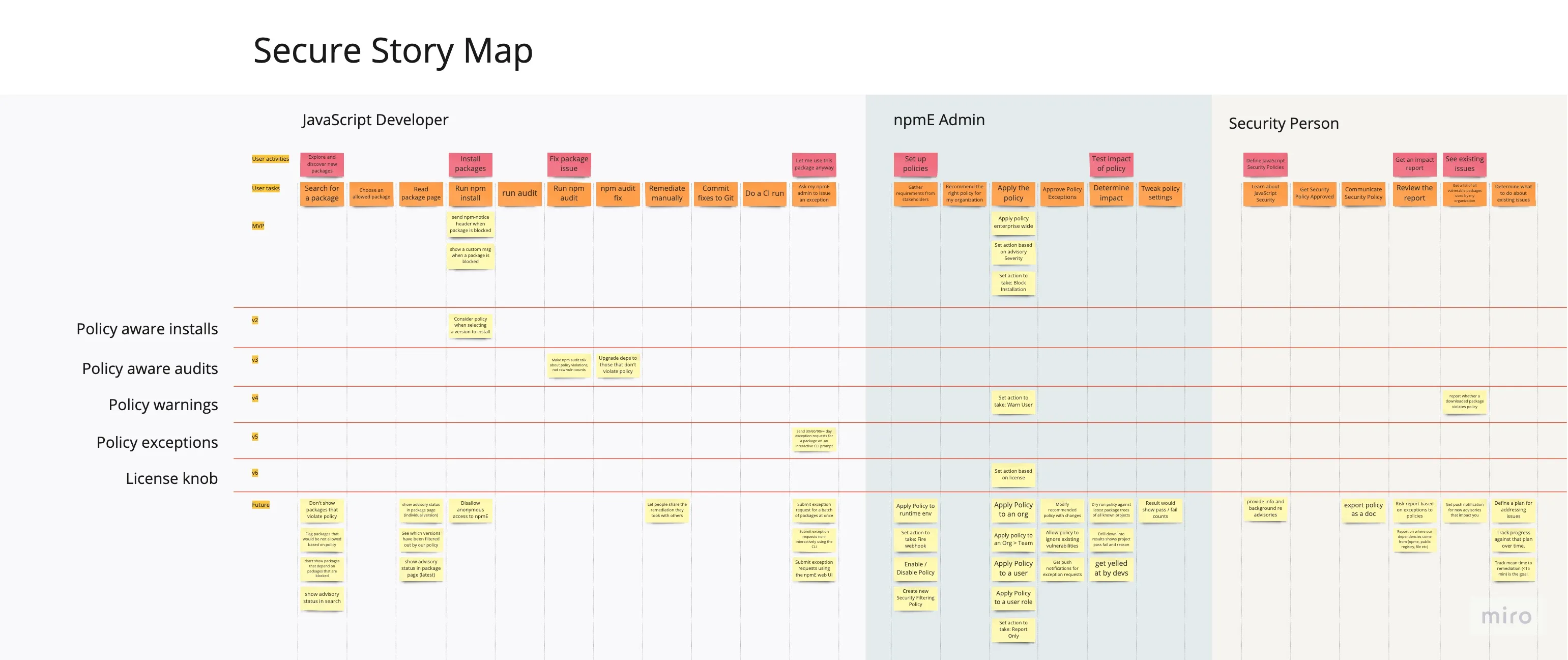

We built a story map which illustrates these needs, alongside the development journey and the accompanying stories.

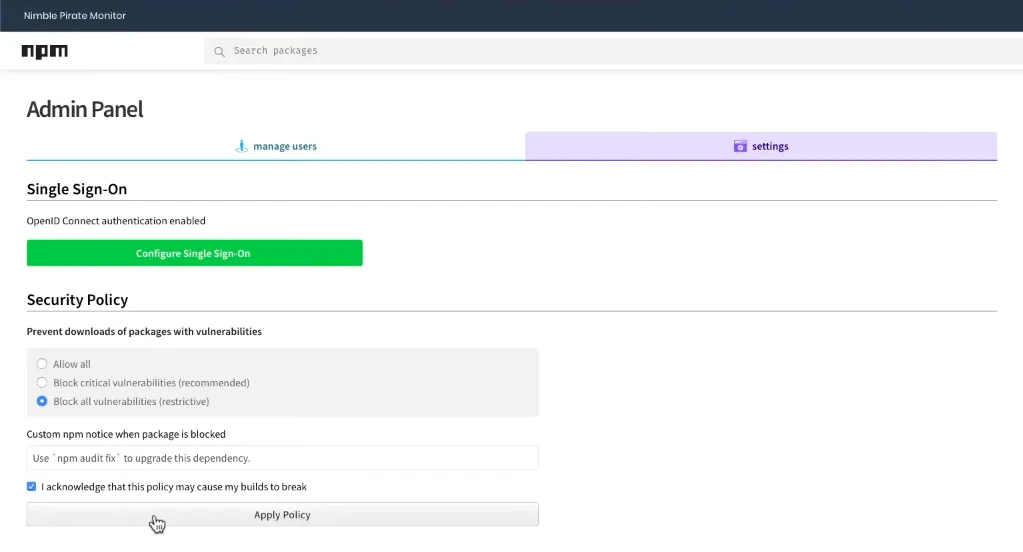

Many competitors in this space have overly complicated policy settings that are difficult to understand and use, so we kept our initial MVP to just three settings:

- Block all packages with vulnerabilities

- Block packages with critical vulnerabilities

- Allow all packages

To meet the needs of the npm Enterprise admin, we built a new admin section in npm Enterprise that lets people configure package filtering.

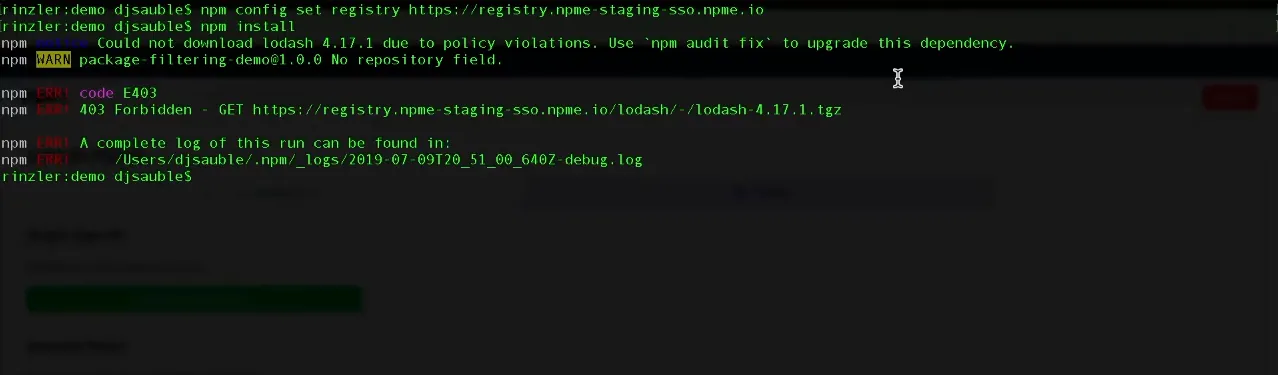

After setting a blocking policy, developer could no longer install those packages. To make it obvious what was going on, we let the npm Enterprise admin set a custom message to display in the terminal whenever packages were blocked.

However, this is only half of a solution. The reason most security products are despised by developers is because they're built for security teams, not developers who have very different needs. Blocking a package means a potential security problem was averted, but it doesn't help developers find a replacement so they can get their work done.

To address this problem, we wanted to have the npm CLI automatically choose a

package version that doesn't violate policy. This way, a developer could just

run npm install, get a replacement package for the one that was

blocked, and be on their way.

To achieve this, we had to make the npm CLI aware of which packages were good, and which were bad. We modified the packument (a JSON object returned by the registry with information about a package, including what version are available) by moving any bad packages to a separate list of "blocked" versions.

Now, the CLI could look at the the list of available versions (now all allowed by policy), and choose the best one. And since we kept the blocked packages in the packument, it could also tell the difference between a package that was not found, and a package that was blocked. A nice side effect of this approach is that legacy versions of the CLI would still work, even though they would lose the ability to distinguish between the blocked and not found cases.

With these changes in place, developers would have a much more pleasant experience. For example, suppose a developer tried installing a specific bad version of lodash.

$ npm install lodash@1.3.1

They would get a blocked message, as before:

npm ERR! code E403 npm ERR! 403 Could not download lodash@1.3.1 due to policy violations. npm ERR! 403 Use `npm audit fix` to upgrade this dependency. npm ERR! 403 npm ERR! 403 In most cases you or one of your dependencies are requesting npm ERR! 403 a package version that is forbidden by your security policy npm ERR! 403 please contact your npme admin. npm ERR! A complete log of this run can be found in: npm ERR! `/Users/admin/.npm/_logs/2019-08-09T20_46_04_225Z-debug.log`

But now they can ask for a list of versions that are allowed by policy:

$ npm view lodash versions

And the resulting list gave them all the information they needed to choose a better alternative.

[ '0.5.0-rc.1', '1.0.0-rc.1', '1.0.0-rc.2', '1.0.0-rc.3', '4.17.12', '4.17.13', '4.17.14', '4.17.15' ]

In fact, they could simply ask for the latest, and npm would automatically install the latest verion of lodash allowed by policy.

$ npm install lodash npm WARN tmp@1.0.0 No description npm WARN tmp@1.0.0 No repository field. + lodash@4.17.15 added 1 package from 2 contributors and audited 1 package in 0.463s found 0 vulnerabilities

This was obviously a very CLI-focused design problem, with just a very simple GUI for configuration, but it's a great example of the importance of not getting in the way of developers.

We also intend to build a remediation workflow that addresses the problem where there is no easy upgrade page to address a vulnerability. Sometimes a package isn't actually a security risk, because it is internally facing, or misclassified, or isn't used in a way that will exercise the vulnerability. Providing developers with the ability to request an exemption will make this even better.